Restoring humans as part of nature

Foraging wild greens in India, removing invasive English ivy on Vancouver Island and what successful forest restoration really needs – plus a new book about milkweed.

What really counts as rewilding?

When we consider the story pitches we receive, one of the criteria we use to choose between yes and no is whether the story is really rewilding. And while sometimes the answer is obvious, that’s not always the case.

Take journalist Sohel Sarkar’s new piece on foraging wild greens in India. At first glance, it’s a food story – it’s not about rewilding at all. Urban food tours in community gardens are a far cry from, say, reintroducing lynx into Scotland. (Still just an idea, but who knows what the future will bring?)

But Sohel convinced us that wild foraging is about redefining people’s relationship to nature. And that is a necessary step for both small- and large-scale rewilding to be successful all over the globe. We hope you agree – let us know in the comments, or by replying to this email.

Stay wild,

Domini Clark and Kat Tancock, editors

How rewilding can help boost food security

In India, an urban foraging movement is helping to restore people's relationship with nature and encourage rewilding projects that incorporate edible plants.

In W̱SÁNEĆ territories, removing invasive English ivy makes way for indigenous plants

Every month, Tseycum First Nation artist Sarah Jim invites volunteers to pull the dense vines choking native species on her family’s land.

Billions have been raised to restore forests, with little success. Here’s the missing ingredient

Forget the tragedy of the commons. To build healthier forests, we need to harness the power of community.

The best (and fastest) ways to replace your lawn with native plants

So you’re ready to start rewilding your yard. But how do you get rid of the grass? Here are three top options.

“Our words have a power that many of us are not yet using. They can paint the natural world as sensing, singing, worthy of life; and they can remind us that we are animals within it, grateful recipients of its gifts, who can offer something in return.”

– Becca Warner, “Why we need new words for nature”

Recommended reads

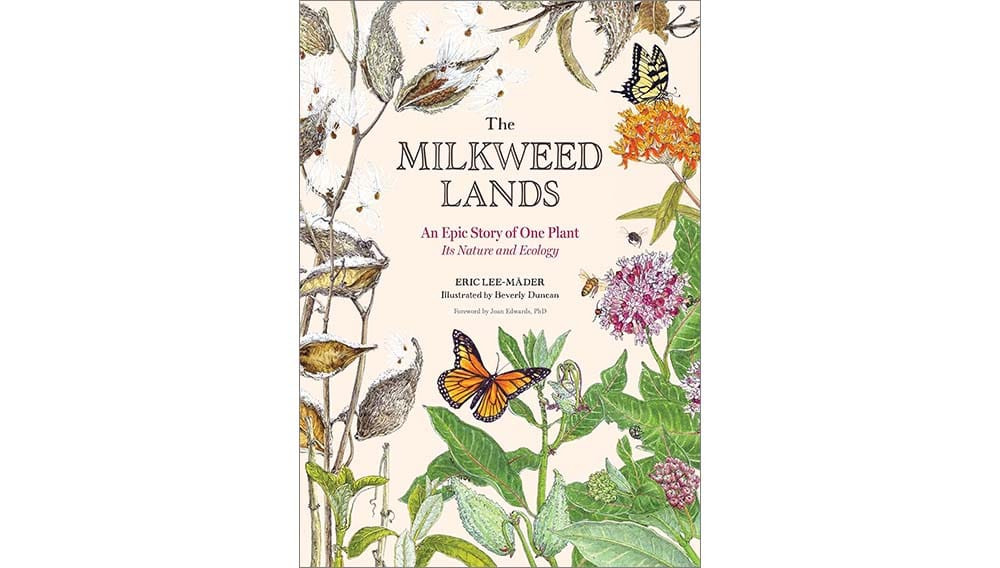

If you live in North America and you’ve done any sort of wildlife-oriented gardening, you’ve probably planted milkweed. The long-maligned genus (a group of about 100 species) made it to the top of the to-plant list thanks to the charismatic monarch butterfly, which needs milkweed for reproduction. (Its picky caterpillars won’t eat anything else.) But have you ever thought of milkweed’s role in the larger ecosystem?

Eric Lee-Mäder has, and in his new book, The Milkweed Lands, he works with illustrator Beverly Duncan to showcase the history, life cycle and relationships of this plant — what he terms an “epic story.” You’ll learn why, exactly, Asclepias is named for a Greek god; meet the various creatures that use it to survive (and help it reproduce); and follow its existence through the seasons, learning how the plant overwinters, grows, flowers and produces seed — only to repeat the cycle again and again.

This book is about milkweed, but it’s also a very accessible botany primer that will help non-experts better understand how ecosystems function and why rewilding is so essential for so many species. “Although this book focuses on the network of one plant, its message of connectivity applies broadly to all species, so critical amid our current global decline in biodiversity,” writes Joan Edwards, biology professor at Williams College, in the book’s foreword. “The Milkweed Lands exemplifies the importance of knowing nature in order to preserve it.”

We encourage you to borrow The Milkweed Lands from your local library or purchase from an independent bookstore.

Elsewhere in rewilding

In big news: The European Union parliament passed the Nature Restoration Law, which aims to restore at least 20 percent of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030. It’s still not a sure thing, but here’s a rundown on what it could involve.

Moving to Africa, bee-keeping is helping restoration efforts at the Ngel Nyaki Forest Reserve in Nigeria, home to a variety of threatened animals including, quite possibly, a small group of the most endangered chimpanzee subspecies. Is there anything those little striped wonders can’t do?

This inspiring story (with wonderful photography) about rewilded former golf courses across the United States may make even the most devoted links enthusiast rethink their hobby. (Gifted link)

In a story similar to that of Ben Goldsmith’s, an Irish couple has found solace and positivity in rewilding after the death of their son. “When we started planting the flowers, it was for Stan.”

And for this issue’s cute animal hit we have …. the pine marten! Known as the taghan in Gaelic, the much maligned weasel* has made a comeback in Scotland. Next up, Wales and southern England?

*Thanks to reader Sara for pointing out that the pine marten is a weasel, not a rodent as we had written originally.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter?

Send to a friend and let them know that they can subscribe, too.

Share your expertise: Do you know a project, person or story we should feature? Let us know.

Just want to say hello? Click that reply button and let us know what you think – and what else you'd like to see. We'd love to hear from you.

Comments ()