Planting the seeds of rewilding

Is celebrity attention helping the cause? Plus, how one woman is turning her lawn into a forest, and how to co-exist with coyotes.

The surprising thing Ed Sheeran and Ginger Spice have in common

It appears rewilding is becoming a cause célèbre, with an interesting cross-section of famous faces recently joining the movement.

The most high profile is Leonardo DiCaprio, who has been active in the fight against climate change for years now. His most recent announcement: a pledge of $43-million to restore parts of the Galapagos Islands.

In second place is Ed Sheeran, who is new to the idea but apparently very keen. He told the BBC in December: “I am trying to rewild as much of the UK as I can.”

Other big names with big plans include Geri Halliwell (aka Ginger Spice) and supermodel Kate Moss.

Is such A-list attention good or bad? On the pro side, all press is good press, and surely planting the seed of rewilding in the minds of Sheeran’s tens of millions of fans (many of whom are young people) can’t hurt.

The downside, some would argue, is that rewilding becomes just another fad – popular until it stops garnering headlines.

Meh. That’s not worth stressing over. The real risk lies in the misunderstanding that occurs when a movement gets boiled down to a buzzword.

As Alastair Driver, the director of Rewilding Britain, said recently: “People will use the word rewilding in a very loose way and it’s really important that we distinguish between what is genuine rewilding, which has a set of key principles going with it, and for example carbon offsetting, just buying up huge tracks of land for planting non-native trees, that is not rewilding.”

One hopes that rewilding’s new celebrity fans understand that their areas of expertise lie elsewhere, and reach out to the many experts and organizations who actually know what they’re doing. DiCaprio, for example, has teamed up with Re:wild and local organizations for his Galapagos project.

At the very least perhaps someone can get this issue into their hands? Halliwell hopes to introduce wildcats into her garden, so she could start by reading about how one New Zealand woman is “killing” her lawn for the sake of biodiversity. Moss, who wants to build a forest, would probably find our excerpt from Hannah Lewis’s new book Mini-Forest Revolution interesting. And who doesn't love a cute animal? In this case, coyotes.

But seriously, does anyone have a contact for Ed or Leo?

Stay wild,

Domini Clark and Kat Tancock, editors

Why I'm killing my lawn to plant a forest

How one New Zealand woman is reforesting her yard as a personal act against climate change that will support native biodiversity, too.

How the Miyawaki Method can help us restore forests faster

In this excerpt from her book Mini-Forest Revolution, Hannah Lewis explains how the Miyawaki Method works and what you need to know to plant your own mini-forest.

What coyotes really want

Coyotes have a bad reputation that's entirely undeserved. Here's what really motivates them – and how we can co-exist in peace.

Invasive species as a metaphor for colonization

In this excerpt from her book Fresh Banana Leaves, Indigenous scientist and author Jessica Hernandez explores how restoration work in the Americas must include building relationships with the lands' original inhabitants.

“Forests long ago made our planet's atmosphere, environment and life-support systems. And they still do it. We mess with their life-support systems at our peril.”

– Fred Pearce, A Trillion Trees: Restoring Our Forests by Trusting in Nature

Recommended reads

If mainstream society’s relationship with nature is broken, how do we go about fixing it? Facts and figures tell the story from the scientific point of view. But at a personal level, it’s the non-rational that needs restoring.

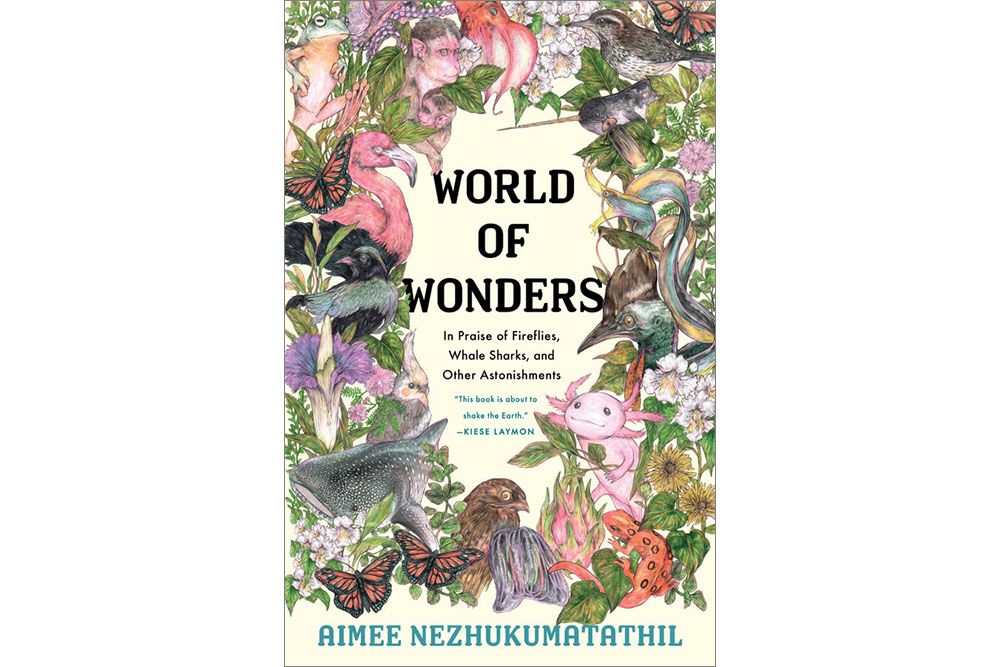

One book that might help is World of Wonders by American writer Aimee Nezhukumatathil. Each chapter is named for a species – including cactus wren, narwhal, corpse flower – and interweaves intricate details about its existence with the author’s own experiences in the United States as a nature lover, a child of immigrants, a woman of colour and a mother of biracial children. Nezhukumatathil is a poet, and while this book is pure prose, the spirit of verse comes through in her unexpected word choices and in the connections she draws between the natural world and the human one.

We have much to learn from nature, she shows us, and listening with curiosity and wonder to the other life forms we interact with is the first step toward healing. “Maybe what we can do when we feel overwhelmed is to start small,” she writes. “Start with what we have loved as kids and see where that leads us.”

We encourage you to borrow World of Wonders from your local library or purchase from an independent bookstore.

Elsewhere in rewilding

Looking for inspiration on how to replace your lawn in a climate prone to drought? We’re a little bit obsessed with this stunning example in Los Angeles. (Here’s that link again on Apple News.)

For those places where the problem is too much water, working with nature rather than against it can mean the difference between liveable communities and frequent floods. Here’s how the Slow Water movement is letting water have its way.

There’s the theory on living side-by-side with predators, and then there’s real life. For one Canadian community, the carnivorous neighbours in question are polar bears. What lessons can we learn from how they coexist?

Connectivity is one of the three C’s of rewilding, and it turns out it applies in the ocean as well as on land. To protect coral reefs and the species who call them home, we need to protect the movement corridors, too.

In what the Guardian jokes “may be one of the slowest-moving conservation projects in history,” 40 red-footed tortoises rescued from the illegal pet trade are being released in El Impenetrable national park in Argentina. It’s been 20 years since a live one was spotted in the country.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter?

Send to a friend and let them know that they can subscribe, too.

Share your expertise: Do you know a project, person or story we should feature? Let us know.

Just want to say hello? Click that reply button and let us know what you think – and what else you'd like to see. We'd love to hear from you.

Comments ()