In this excerpt from his book Lawns into Meadows, landscape designer Owen Wormser shares some secrets to creating a meadow you'll love.

A good meadow design takes into consideration your climate, the qualities of the plants you choose, and how tall you want your meadow to be, among other things. You also want plants that will take turns flowering throughout the growing season, so your meadow is always in bloom. One more thing: Trust the process. Plan your meadow, plant it, and then see what turns up. Nature has a way of sorting things out.

Use plants native to your area

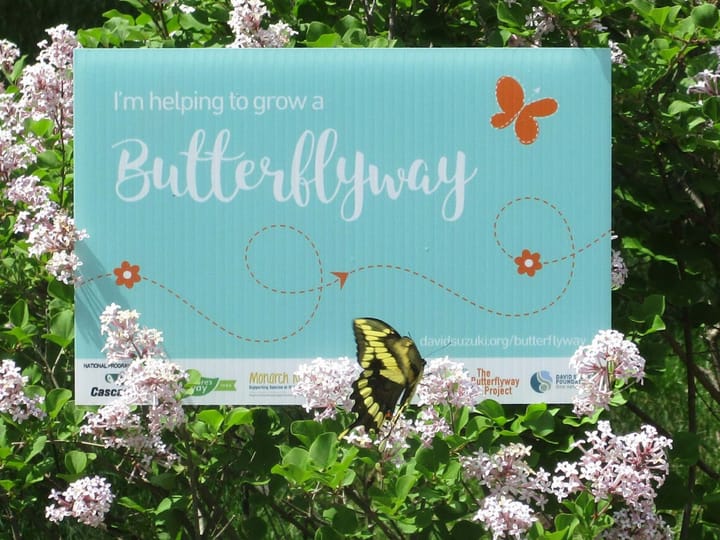

The sturdiest plants are ones that have evolved to handle your environment. Natives have also become an integral part of the local ecosystem, like the milkweed that monarch butterflies rely on to complete their life cycles. The ability to support these complex relationships is part of what makes a meadow regenerative.

I generally use plants that grow locally, but I’m not averse to using regional ones because they can be easier to find, which gives me more design options. While I don’t plant non-natives because they can become aggressive and overwhelm a meadow, not all of them are bad. Some, like daisies, have naturalized and live in relative harmony with the local ecosystem.

Choose seeds or plugs, or both

The size of your meadow can determine whether to plant seeds or plugs, which influences your design process. I generally sort meadows into two categories: The field by City Hall in Northampton is a meadow garden, which means it’s small enough to be planted from plugs, which come in trays and are tinier than the average size plants in nurseries. They also grow much more quickly than seeds. Seeds are well-suited to larger traditional meadows.

It’s easier to design with seeds because they’ll do much of the work for you. Seeds are sensitive enough to sort themselves out based on microclimates and small variations in soil quality, moisture, and more. You may find, for instance, that butterfly weed establishes itself in one part of a new meadow because it’s slightly sandier there, while the indian paintbrush you planted at the same time sprouts on the other side because it likes the soil density.

Planting from plugs is a more deliberate process, since you’re the one who controls where they go. Before ordering any plugs, you’ll want to work out a design concept. The goal is to spread the grasses and flowers as evenly as possible, creating a randomized effect while giving each plant enough room to grow to maturity. You can fine-tune the spacing once it’s time to plant your plugs.

As for using seeds and plugs, I sometimes recommend using plugs in areas you want to grow faster, like a strip along a well-used walkway, and using seeds everywhere else.

Grasses first

Over my many years of planting gardens and meadows, I’ve come to appreciate that while blossoms come and go, grasses are around for the duration. Grasses give fields the look and feel of a meadow, and are the reason they’re often beautiful in the dead of winter. At times I’ve been so struck by the sight of grass husks iced by frost and glinting in the early morning sunlight I’ve had to pull over my car to take it in.

Since grasses ground a meadow visually and are the dominant plants, choose them first. Keep in mind that they need to coexist with neighbouring meadow flowers; you don’t want grasses that spread too aggressively and will force out the other plants.

Grasses tend to be categorized as cool-season or warm-season plants. Cool-season grasses grow quickly earlier in the growing season when daytime temperatures average 60 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit (15 to 24 degrees Celsius). In the full heat of summer, they often go dormant, or stop growing, to conserve energy. This type of grass is regularly used for lawns, often includes non-native species, and tends to form into mats. The density of their roots explains why meadows made of cool-season grasses tend to support fewer wildflower species.

If you live in a very cold part of the country, say in Wyoming, Minnesota, or northern New England, you may want to rely more on cool-season grasses. But for most of the country, warm-season grasses work best. These are the most common native meadow grasses and make up the backbone of my meadows. They do most of their growing when temperatures regularly reach above 75 degrees Fahrenheit (24 degrees Celsius) and usually grow in clumps, which makes room for other plants.

I include at least two, and as many as three or four, warm-season grasses in my meadows if I’m planting a larger meadow. I tend to use one or two perennial grass species, and no more than three in a small one. No matter how large the meadow, I make sure at least 35 percent and as much as 75 percent of the plants are grasses so it looks meadow-like. The exact ratio is really up to you.

Little bluestem grass is my go-to when conditions warrant, like soil that’s very well drained and dry. Switchgrass, side oats grama, and prairie dropseed are also excellent warm-season grasses. But cooler-season grasses have their place, too. I often add at least one, like Virginia wild rye or nodding fescue, because they show up early in the spring and mature quickly. This means they keep your meadow looking green when the rest of your young grasses and perennials are just getting started.

Find plants that are about the same height

It’s much easier to achieve a lasting balance this way. Most of my meadows are between two and four feet tall. While taller plants have their place, particularly in large spaces or prairie restoration projects, I rarely use them in smaller, suburban meadows because they can overwhelm a house and make a field look messy. Taller plants can also be more prone to flopping over in heavy rains or wind, leaving behind tired-looking, flattened scapes.

I occasionally bend my own rule and include a few shorter flowers if I think they can add a splash of colour without getting lost or taken over. Another way to manage a mix is to separate out seeds for taller plants, like perennial sunflowers or Joe-Pye weed, so you can plant them along your border or in a corner and they don’t detract from or dominate the rest of your field.

Choose a variety of flowers

I typically include 15 to 25 flowering species when planting a large meadow from seed, and make sure at least one or two will be blooming at all times. If a few of them fail to sprout, no problem. You have enough back-up perennials to take up the slack.

You won’t need as many different flower species if you’re planting a smaller meadow garden, because it will look too busy and chaotic. This holds true whether planting from plugs or seeds. In small meadows, I usually include between seven and 15 flowering perennials.

Pick colours that look good together

Finding flowers to match site conditions is an important consideration, but so is choosing what you like. I know one person who was open to every colour but white. She couldn’t stand the thought of a field of white flowers, so we didn’t plant any. Another client had a just-big-enough-for-a-meadow clearing that barely allowed in the requisite half day of sunlight. He gave me the go-ahead to bring on a riotous blend of bright red bee balm and cardinal flowers, as well as purple coneflowers, perennial sunflowers, and deep orange butterfly weeds. A woman who lives in a purple-gray ranch house wanted to accent it with purple, pink, blue, and white flowers, and it really did improve the overall look of the house.

Adapted with permission of the publisher from the book Lawns into Meadows by Owen Wormser, on sale now from Stone Pier Press. All photos courtesy Owen Wormser.

Comments ()