A concerted and collective effort has helped populations rebound of this predator native to Spain and Portugal.

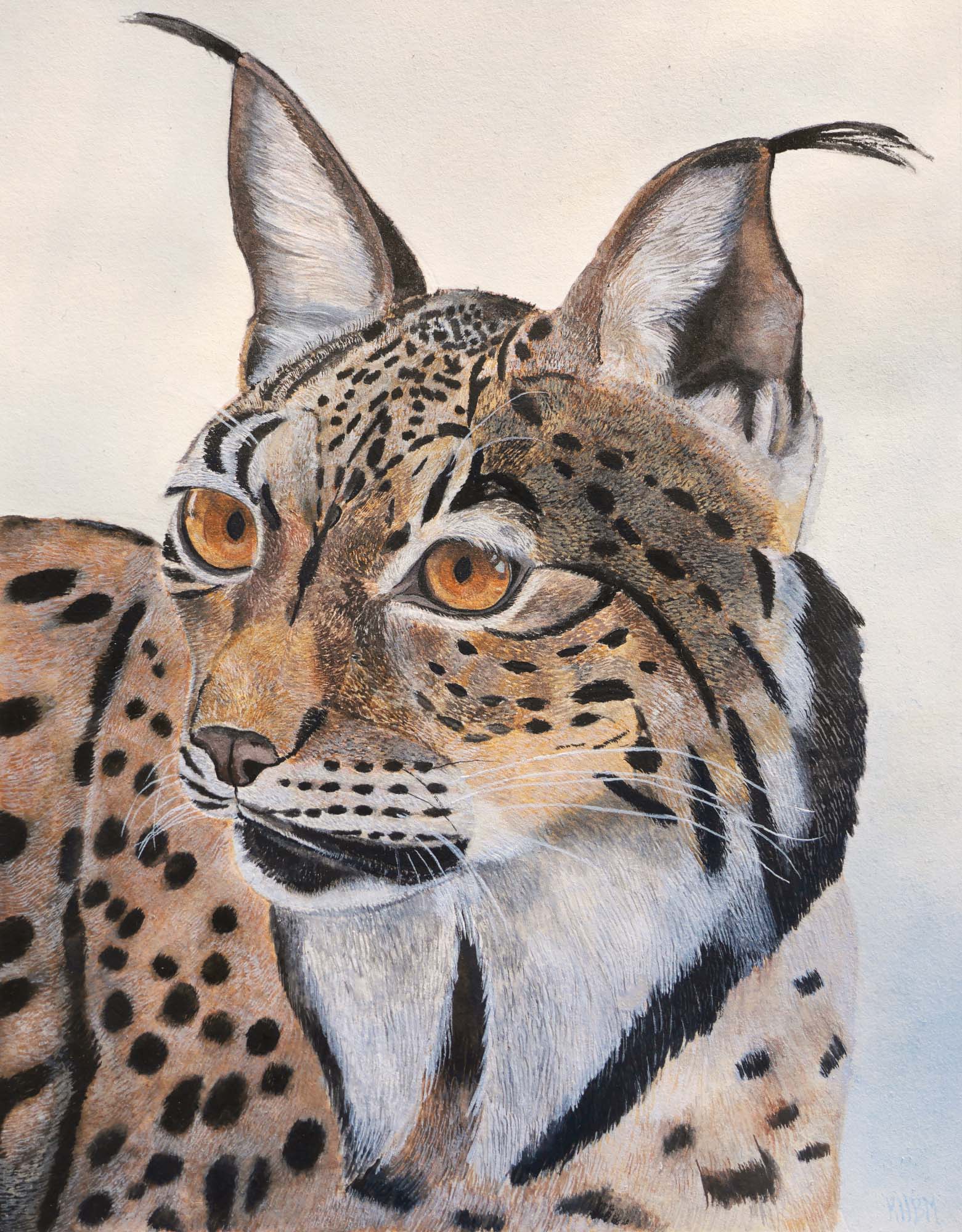

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) was listed by the IUCN as being critically endangered, with the unfortunate sobriquet of the “world’s most threatened cat.” There were thought to be only 52 wild individuals left of this truly beautiful animal, an endemic cat species of southern Spain and Portugal and one of two lynx species found on the continent, the other being the much more widespread European lynx (Lynx lynx).

The Iberian lynx had been in decline for many years. Habitat loss and human activities were causing a severe impact, as well as disease outbreaks among its principal prey, the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). The remaining lynx existed in just two genetically isolated populations.

We humans often cause destruction in the natural world, but we also have the capacity to do great things – and that is exactly what has happened in the past 22 years. Conservationists, politicians, landowners, scientists and communities have come together to save Lynx pardinus, and they have been extremely successful. From that nadir of just 52 there are now more than 2,000 individuals living in the wild in Iberia.

The work started in 2002, when it was realized that drastic action had to be taken. A captive breeding population was set up to try and safeguard the species, the idea being that genetically robust populations could be built up for release, not only to reinforce remnant populations but also to create new ones. Work was also implemented on boosting the wild rabbit population as well as the habitat required by both them and the lynx. Crucially, this involved creating links or corridors between the two existing lynx populations and the new release sites. One of the problems for the lynx had been that the two population groups were effectively cut off from each other – they were islands of ever dwindling genetic diversity. For the project to succeed, there couldn’t be islands: populations had to be able to expand, mix and disperse. Rewilding landscapes in key areas by allowing and encouraging natural vegetation to develop played a key part in the success of the project. But it wasn’t the only key part. The people who were to share the land with lynx were also essential.

One of the most important tools in conservation is communities. If you can get the local community to buy in to what you are doing, to get on board with your aims, then your chances of success increase substantially. In the late 1990s, although legally protected, Iberian lynx were still commonly treated as vermin: animals were frequently shot and trapped, adding to the pressures the species was already facing. But now the lynx is an iconic species proudly welcomed by local communities. Road signs as you enter villages and towns declare with enthusiasm that they are home to the Iberian lynx. Schoolchildren help with the release of captive-bred animals, and politicians of all parties are happy to be involved in this good news story.

There are occasional problems – animals are still illegally killed – but local communities are now quick to denounce those involved and the Spanish state is swift and thorough in its investigations. Those that do transgress are soon caught and face not only very large fines but years in jail as well. The message is clear: the communities want their lynx.

The captive breeding program has been very successful and several new population nuclei have become established, with the released animals soon breeding and producing wild-born kits. As these new populations have grown, so too has a lynx tourism industry that brings local jobs and money to the communities in which the animals live. People from all over the world want to see these iconic animals and there are now plenty of tour operators and guides to help them do so, as well as plenty of places for them to stay and eat. The conservation success of the project has not only benefited the lynx – it has also benefited the local communities whose continued support is still vitally important.

The Iberian lynx still faces threats, though, the most serious – and deadly – being roads. At the beginning of the project, large amounts of money were spent on fencing work and underpasses along the roads both where the two remnant populations were residing and near future release sites. Lynx warning signs have also been erected along roads, encouraging drivers to slow down and be aware that lynx are about. But as the population grows, as the range of these cats expands, as animals move and disperse, they come into ever-increasing contact with more and more roads. It is a threat that increases commensurate with the success of the project.

A lynx named Ulises. Photos: Kate Boyce-Miles.

Between February 2024 and October 2024, 41 Iberian lynx were killed on the roads of Spain, three of them in just a five-day period at the end of September. These are the ones that are known about; there are certainly more, including animals that managed to crawl under cover and die out of sight. Numbers like these are not sustainable and threaten to undo the fantastic work that has bought this animal back from the brink.

Lynx collision blackspots – locations where there have been multiple casualties –are being identified, and mitigation methods are being put in place, such as installing new fencing leading to underpasses. In some places, new technology is helping. Captive-bred animals are released wearing radio collars so that their movements can be tracked by biologists, and road signs are being deployed that can detect the signals from these collars and flash a warning to oncoming drivers. More work needs to be done, but it is hoped that the high numbers of road casualties seen this year can be greatly reduced.

The Iberian lynx is a conservation success story, a fantastic example of how effort and willingness from a wide range of people can make a difference. To go from 52 individuals to 2,000 in just over 20 years is phenomenal. This success has now been recognized by the animal’s official IUCN status, which has moved from “critically endangered” to “endangered” and now to “vulnerable.” It is a good trajectory, but it mustn’t be forgotten that the status of these cats is indeed vulnerable and the recent spike in road deaths illustrates that perfectly.

Iberian lynx are beacons of hope, the living proof that we can get conservation and rewilding right. The project should be a lesson to all involved in these kinds of projects. Involving a wide spectrum of groups is important, getting the local community on board is important and benefiting the local community is important – as is planning for challenges caused by success.

There are some that even today still seek to deride the project. Headline-grabbing stories about livestock predation, even when untrue, can damage public perception. This is why involving the local community from the very beginning of any project like this is so important. Let them buy into it, let them be involved and have their concerns listened to and addressed. When we do that, false stories spread by those with agendas have far less impact.

Conservation and reintroduction of predators can be a polemic issue, an issue that can be exploited by those with vested interests or by politicians desperate for votes. The wolf is the classic example of this, be that in North America or in Spain. Coexistence with predators is essential if rewilding is to be truly successful, and the Iberian lynx is a great example of how it can work. There are challenges – there will always be challenges – but challenges can be overcome. This exciting project has brought back a species that was heading for the exit door.

Main photo: Kate Boyce-Miles

Comments ()