Kelp forests are critical ecosystems and effective carbon sinks, too – but they're under threat around the world. This team of free divers and scientists is trying to make a difference, one purple urchin at a time.

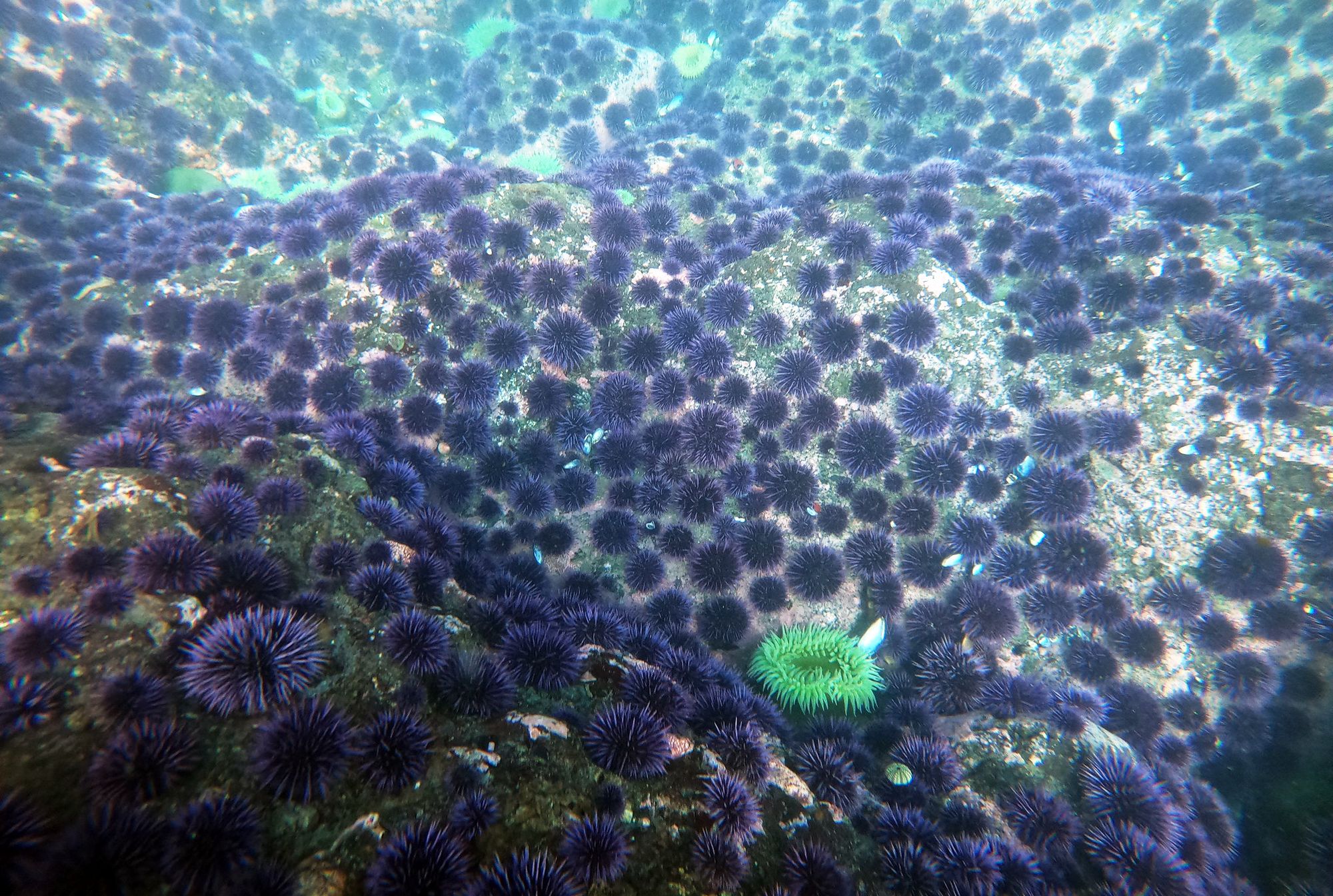

Looking out from the beach in Pacific City, Ore., the ocean is expansive and serene. But dive underneath these waters and you’ll see that the kelp forests that once streamed in the current are being replaced, year after year, by ominous clumps of purple urchin. “The ocean is beautiful, but most people can't see the decimation that's occurring underneath,” says Talya Semrad, a competitive free diver. “So, something that appears to look healthy and pristine isn't. It's really up to us, the people who are getting in the water regularly, to make noise about it.”

Centuries ago, purple urchin lived in balance with sea otters, sunflower sea stars and kelp forests in the Cascadia bioregion along the northwest coast of North America. This temperate landscape encompasses some 4,000 kilometres (2,500 miles) of coastline and includes the ancestral and current homelands of numerous Indigenous nations, among them the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians. Urchins feasted on kelp, but their numbers were limited by the appetites of sunflower sea stars and of voracious sea otters, who must consume a quarter of their body weight each day.

Sea otters were hunted to the brink of extinction from the mid-1700s to the early 1900s, when maritime fur trading caused population levels to plummet to about 2,000 from an estimated high of between 150,000 and 300,000. In the 1970s, efforts to reintroduce these marine mammals succeeded in Washington, California and British Columbia, but failed in Oregon; scientists are not sure why. Then, from 2014 to 2016, a widespread wasting syndrome driven by warming ocean waters severely reduced the population of sunflower sea stars, which are now considered critically endangered. Purple urchins, left unchecked by predators, boomed. Meanwhile, Oregon’s Orford Reef has experienced a 10,000 percent growth in purple urchin since 2014. They devour the kelp then, when food becomes scarce, enter a dormant, zombie-like state, and can survive for years without eating.

Increasingly, under the waves, kelp has dwindled, overtaken by the hardy, hungry urchin barrens. This is a problem not just for local ecosystems, but for efforts to fight the climate crisis, too. Kelp “sucks up carbon faster than pretty much anything on the planet,” says Tom Calvanese, a fisheries scientist at Oregon State University. Figuring out the best way to reduce the urchin population will help kelp forests fulfill that role.

To most coastal dwellers, changes to these marine habitats are nearly invisible. With water temperatures ranging from 7° to 14°C (44° to 58°F), surveying what’s happening below the surface is a chilly proposition. Yet local free divers, clad in 7-millimetre-thick hooded wetsuits, take to these waters in search of rockfish, lingcod and slow-moving Dungeness crab. Now, they’re participating in rewilding efforts, too.

Semrad is a co-investigator on a new study that scientists and divers alike hope will preserve remaining kelp and clear the way for new underwater forests. Calvanese is spearheading the research, matching free divers such as Semrad to five urchin-rich areas on the Oregon coast. Their first task is an urgent one: culling (crushing and killing) purple urchin in place – with the blessing of state officials – to preserve the tiny amount of kelp that remains. Divers will also help Calvanese gather data about urchin reproduction, culling methods and other monitoring projects.

If their findings suggest culling urchin is effective – and Calvanese says that so far, this is the case – the next step is kelp outplanting. His plan is to allow natural fibre lines to be seeded naturally in a kelp-rich environment, then placed in restoration areas to help kelp re-establish itself. (Kelp reproduction is a complex process that requires a release of spores and, ultimately, the development of a juvenile sporophyte, which, when mature, is anchored underwater by a root-like structure called a “holdfast.”) The hope is that these efforts will lead to the re-establishment of kelp forests at study sites, as well as to new information about the best methods for rewilding kelp.

“The fun thing is that if we manage to cull [the urchins] this year, next year we will see a huge growth spurt,” Semrad says, “because kelp is an annual.”

The project has already garnered attention above the waves, including a donation of halibut from some locals, one of whom dubbed the team “kelp forest defenders,” says Calvanese, a former commercial diver. “He said, ‘I'm a commercial fisherman and kelp forests are really important to my livelihood. So I support what you guys are doing.’” As for being labeled a defender, Calvanese adds, “I love that term and we've run with it.”

Healthy kelp forests support species diversity in marine ecosystems by providing both a source of nourishment and a habitat, and could cement the success of sea otter reintroduction efforts on the coast – another step in a rewilding process whose ultimate aim is an ecosystem that can, once again, maintain its own balance.

Bob Bailey, current president of the Elakha Alliance (“elakha” is a word derived from the Clatsop and Chinook words for otter), recently released results of a feasibility study for reintroducing otter, and says a kelp habitat would provide a hunting ground for the marine mammals, who, in turn, could keep urchin populations in check.

“Our project has helped to focus attention on the need to protect kelp ecosystems. In our view, sea otters are part of a long-term solution,” Bailey says. And whatever the best techniques end up being, Calvanese hopes that his research will continue to garner community support from Indigenous people, coastal dwellers, sport and recreational divers and other scientists, adding to global efforts to preserve and rewild kelp that aren’t dependent on current borders.

Along with Calvanese, scientists and nonprofits in kelp-rich coastal areas from the Pacific Northwest to New Zealand and Australia are experimenting with kelp outplanting techniques and urchin-culling methods. Their efforts are geared, ultimately, toward addressing the mammoth problem of climate change.

“I think it's important that we acknowledge the enormity of the issue, but also don't allow ourselves to be paralyzed by it,” Calvanese says. He adds that he finds hope – and motivation – in his work. “Really, all we have is each other and our commitment to work together toward a common goal. Even if we don't all completely agree.”

Comments ()