Want to support pollinators beyond your yard? Here’s how to do it

A pollinator corridor can bring butterflies, bees and neighbourhoods together. Here’s how to get one started in your community.

You’ve rewilded your yard (if you have one) and turned it into a pollinator paradise. You’ve watched the butterflies come back and the bee population grow. And now you want to do more.

Across Canada, gardeners just like you have grown a network of communities that are expanding pollinator habitat one plot of land at a time. The David Suzuki Foundation recruits and trains these volunteer Butterflyway Rangers to take action locally, as part of the citizen-led Butterflyway Project.

Each Ranger’s self-directed initiatives vary in size and scope, but their primary focus is the creation of a Butterflyway, a series of 12 or more habitat gardens in close proximity. (Some of these gardens are even in canoes.)

To find out how you might be able to amplify your impact beyond your own front yard – no matter where in the world you live – we spoke with three seasoned Rangers. Here they share their tips on growing gardens and community, at any scale.

Get online

When Gwen Chapman set up the Brantford Butterflyway Project in Southern Ontario, her first step was to start a Facebook group to communicate with anyone who wanted to be involved. Helga Jakobson in Winnipeg started with an email address and Instagram account for information sharing, while Sean Cronin built a website to detail his initiatives on Nuns’ Island in Montreal.

Whatever your preferred platform, an online home base allows people to learn about what you’re doing and how they can help.

Enlist the eager

Helga, a sustainability coordinator and former landscape designer, knew her community was filled with people planting pollinator gardens – she just had to identify them. She put out a call in her neighbourhood association’s newsletter and distributed 1,000 flyers to nearby households asking people if they wanted to be part of a Butterflyway. “A lot of people were already really eager,” Helga says. “They just needed a little bit of support, guidance and information.”

She met with nearly all of the 85 people who responded to her callout in order to look over their yards and give them advice on which plants to add to attract pollinators, then registered their spaces with the David Suzuki Foundation as Butterflyway gardens.

Give away plants and seeds

To jumpstart community involvement in the Brantford area, Gwen and her team of five core volunteers did a big giveaway for their Facebook followers. They purchased seedlings from a nearby nursery with money received from a community grant, then created and distributed 50 lots of six or seven native plants each, plus dill and parsley seeds.

In Winnipeg, Helga set up a free-plant stand outside her house, pulling up plants from her rewilded meadow-like yard. She also gives away packs of seeds collected from native plants.

Recruit new people

To reach people who aren’t yet aware of the importance of pollinator habitat – or who simply don’t know how to contribute – find places where you can share details about why and how they can help.

Sean presents workshops at his local library and a children’s camp, and hosts a photo hunt for kids to find different plants and wildlife in the neighbourhood. Gwen goes into schools and visits gardening clubs, and also sets up information booths at local Earth Day events and community festivals. “A lot of being a Butterflyway Ranger is being there and ready to help and support people who are interested,” says Gwen.

Show results

The David Suzuki Foundation tracks affiliated pollinator gardens on its website, but making your own map can further help build your local community through social proof, by showing neighbours how many others nearby are also involved.

The Brantford Butterflyway Rangers, for instance, use Google Maps to maintain a listing of the pollinator gardens within their region, while Helga designed an infographic of her neighbourhood. “I made a honeycomb grid overtop a street view image,” she says. “I filled in where the Butterflyway houses are and show where the gaps need to be filled in.” She says people would notice that their neighbour is in one of the empty zones and ask if they’d add native plants to their gardens to help fill in the map.

Find public land

Sean found his first public garden location across the street from his house, but for his next five gardens he used Google Maps to search for more city-owned green spaces in his neighbourhood. “I saw there were a lot of spots that were just grass, where you could put gardens,” he says.

“You want it to be somewhere where people frequent, where they’ll enjoy it the most,” says Helga. Once you’ve chosen a spot, you’ll have to consider things like if you’ll need to put in raised beds, what plants will work best in that location and how you’ll water them. “With creativity and perseverance, any spot can be a good spot.”

Work with your municipality

To plant pollinator habitat on public land, you’ll need permission from your local government. Some jurisdictions have established programs that you can apply to, which is what Sean did in Montreal. “I wish I’d known it was that easy,” he says.

If you’re unable to find a program in your area, get in touch with your local councillor. They should be able to direct you to the right department or guide you in bringing a request to council.

That’s what Gwen did when she wanted to get the bylaws in Brantford changed to allow and encourage more native plantings. Her group of volunteers now manages more than 10 public gardens, but it took time to make it happen. “You have to wait for stuff with the city,” she warns.

Helga experienced something similar in Winnipeg, where it took three years from initial idea to breaking ground on her community garden. “It takes a lot of patience and tenacity,” she says. “But it’s almost done, and it feels really valuable and important.”

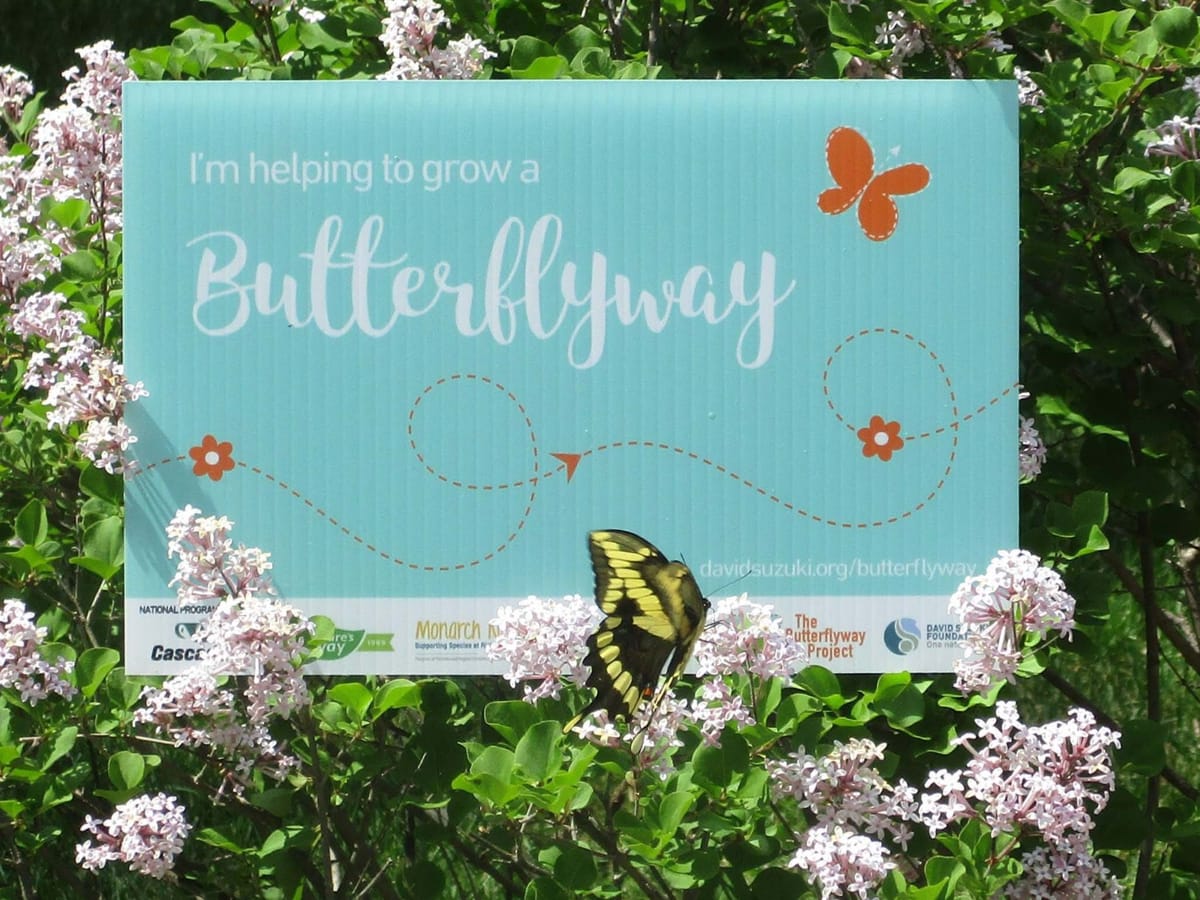

Put up signs

Helga found that providing lawn signs helps home gardeners feel committed to the cause. “Everyone wanted a sign for their yard,” she says of the 85 people who initially signed up in her neighbourhood. “The signs help spread the word as well – like advertising for us.”

Gwen points out that signs are also a useful educational tool. “People think that you’re just growing weeds otherwise,” she says.

The David Suzuki Foundation provides signs to registered Butterflyway Rangers, but both Helga and Gwen also had their own chloroplast signs printed to meet high demand.

Apply for grants

Costs for plants, soil, gardening tools and other materials can add up quickly. But you don’t necessarily need to pay for them on your own.

Sean has received grants from the city and from a financial services provider. “I just filled out a form, had a little presentation,” he says.

The grant that Gwen received, which she used for that initial plant giveaway, came from a local community garden nonprofit.

Do your research to find available grants from governments, corporations and nonprofits in your area.

Get into fundraising

Another avenue to cover costs is to fundraise. Gwen puts out a donation jar at her information booths and usually collects enough to cover the cost of the booth, plus a little extra for getting more plants.

Other possible fundraising activities could include plant and seed sales, by-donation workshops or raffles.

Become a Butterflyway Ranger (or your local equivalent)

You can absolutely go out on your own and start rewilding and engaging the community – and you should! But you can also look for existing local groups to join – including, if you’re in Canada, the Butterflyway Project, which can provide education, resources and extra support.

“Having the stamp of an organization behind you makes it easier to reach out to neighbours and other organizations,” says Helga – and to “get people to listen.”

Comments ()