The scientist who tells stories through botanical illustration

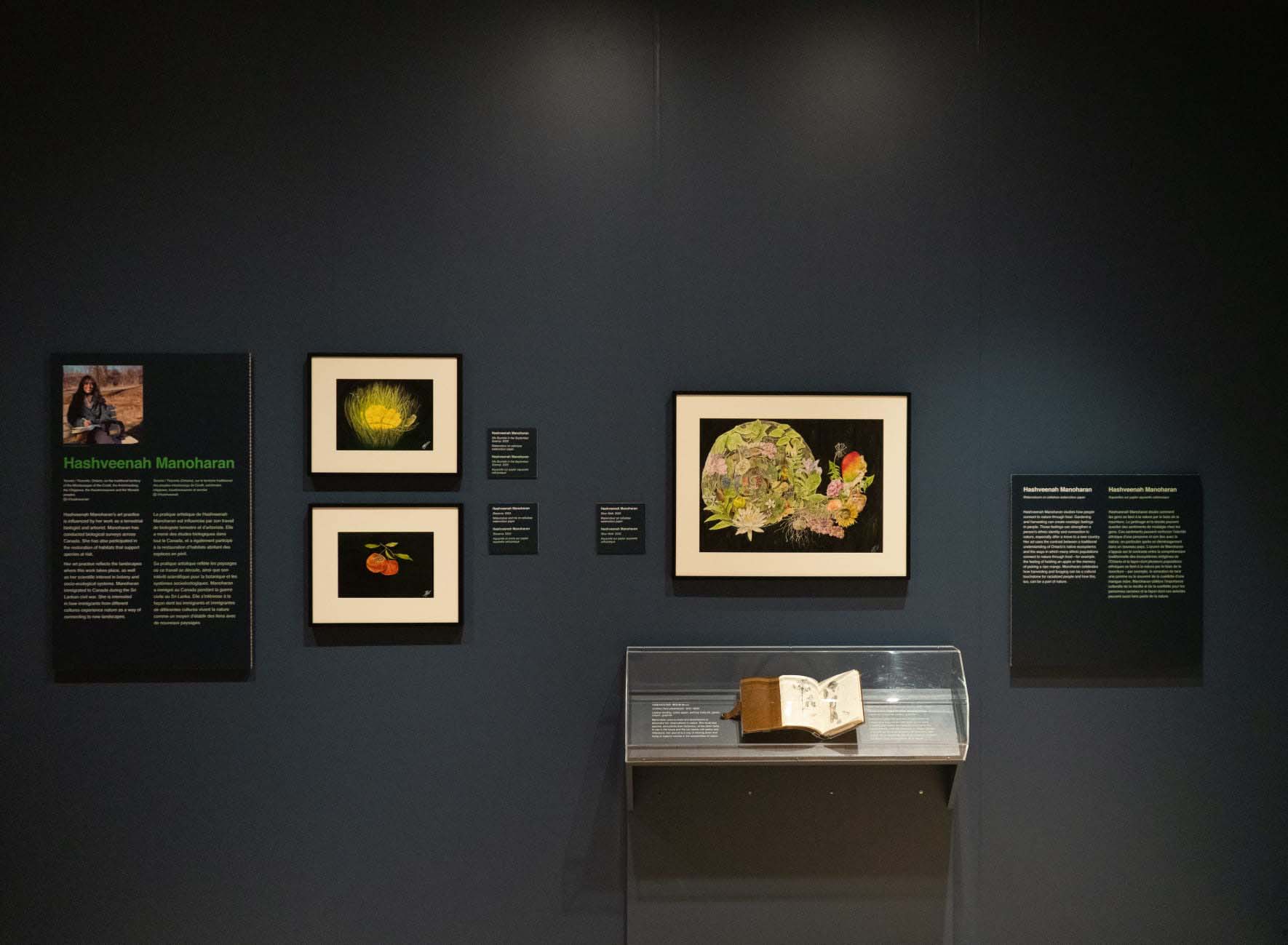

In using drawing as a way to understand nature, artist and ecologist Hashveenah Manoharan discovered her culture, her history and herself.

Even if you don’t know their names, you’re probably familiar with the works of Maria Sibylla Merian and John James Audubon. Merian painted images of flowers and insects in the 17th century, and Audubon, well, he’s the bird guy. They’re but two of the artists who established the gold standard of scientific illustration – beautiful, highly detailed, factually accurate depictions of some of the millions of species on Earth.

“Scientific illustration has a simple goal of trying to showcase different parts of a species for practical utilitarian purposes,” says Toronto-based artist Hashveenah Manoharan, a recipient of the Rewilding Arts Prize presented by the David Suzuki Foundation and Rewilding Magazine. Usually, drawings of the seed, the sprout, a bud, the flower and the full plant are organized neatly beside each other. Bird illustrations often include both a male and female of the species.

Manoharan, though, uses the same visual language of scientific illustrations to tell a different story. Instead of “objectively documenting” plants and animals, her compositions are about personal history and cultural grief.

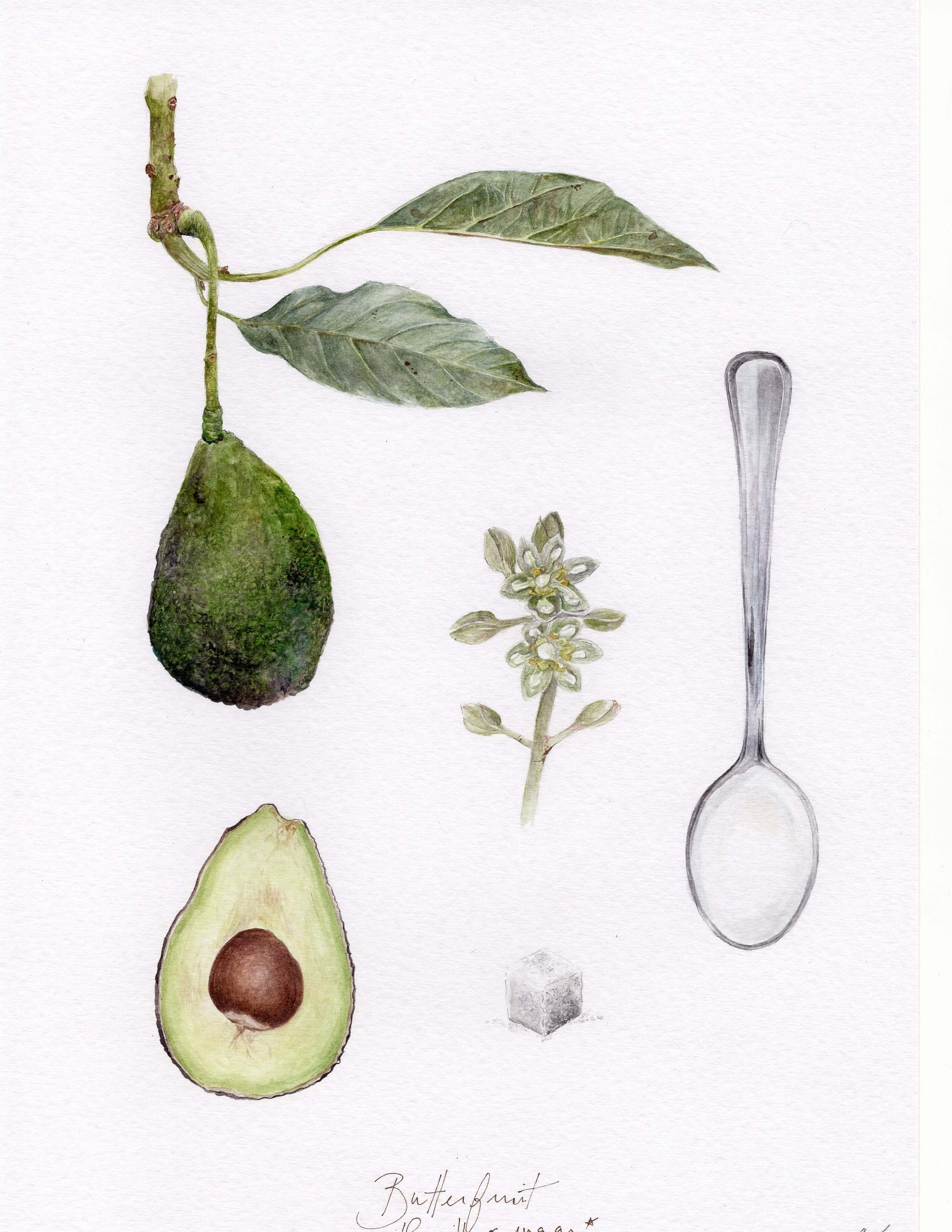

“Butterfruit” and “Farmer’s Friend” by Hashveenah Manoharan, both from the Butterfruit series. Images courtesy the artist.

At first glance, Manoharan’s Butterfruit series looks like typical botanical paintings. Each watercolour shows two to five objects lined up in tidy formation. But take a second look and you’ll notice more than flora.

For example, along the bottom of “Farmer’s Friend” lies a leek. Above it, you see not various stages of its flower in bloom, but a farmer’s sickle, a snail shell and a dark bird with copper-coloured wings and red eyes. The bird is the greater coucal, a crow-like cuckoo widespread in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

When British colonizers arrived in the area, they hunted the bird, assuming it to be similar to the pheasant because of its colour, size and long tail. It didn’t taste very good, though, so they called it foul and devilish, and the bird took on negative associations.

Around the world, in the history of ornithology and botany, the colonizer’s experience often overwrote local knowledge. Scientific illustrations aided in advancing European identification and naming at the expense of native nomenclature. Known as senbagam in Tamil, the greater coucal was actually considered a symbol of good fortune.

The story Monaharan tells in “Farmer’s Friend” is of the auspicious position the senbagam holds in Sri Lanka, where Monaharan was born. There, the bird protects crops by eating the pernicious giant African snail.

“I wanted to take not just the specimen but also the stories around it, the cultural associations,” says Monaharan, many of whose Tamil family members have farmed leeks. Going beyond the utilitarian purpose of documentation, the self-taught artist includes legacy and lore in her work, positioning history and practical ecological knowledge together.

In doing so, Manoharan critiques the colonial history of European empires’ attempts to tame, categorize and own nature – as well as whole civilizations. “The scientific format and the scientific text is what we treat as truth and fact, and we respect that form,” says Manoharan. “So we respect all these white people who went into other countries and extracted information. They completely ignored generations of ecological knowledge. I didn’t want to be a part of that practice.”

Manoharan isn’t just talking about her art. She’s also an ecologist, arborist and biologist – disciplines that stand on the shoulders of that colonial past.

Her art practice began as a means of identifying, remembering and deepening her relationship with the wildlife she interacts with as a scientist. “Art has been a way for me to get better at my job,” says Manoharan. “Drawing helps me distinguish one plant from the other.” Before she “knew better,” she thought Merian, Audubon and their ilk were the pinnacle of nature art. “When you work in nature and you also like art, the instinct is to copy, to render,” she says.

“Sassafras” and “Teatime” by Hashveenah Manoharan, both from the Butterfruit series. Images courtesy the artist.

The transition from sketching for documentation to art as expression and commentary came after Manoharan read the poetry of Mary Oliver. In her book Our World, Oliver writes, “Attention without feeling, I began to learn, is only a report.” It was a turning point for Manoharan, who started including commentary, poetry and other notes in her field journals.

Now Manoharan’s watercolours assert personal stories and cultural history.

The titular artwork of the series, “Butterfruit” – named after the Tamil word for avocado – displays a realistic rendering of two avocados. There’s a full one attached to a branch and one cut in half to reveal the pit, plus the flower of the fruit.

However, alongside them are not more growth stages, but a spoonful of milk and a sugar cube. It seems like an unusual pairing unless, like Manoharan, you also grew up eating bowls of sweetened avocados for breakfast. In Sri Lankan, Filipino and other homes in Southeast Asia and around the world, this is a common dish.

By showing these items together, Manoharan tells a story of her childhood and culture. “This plant that I knew by name and function in one country had a completely different identity in another,” she says.

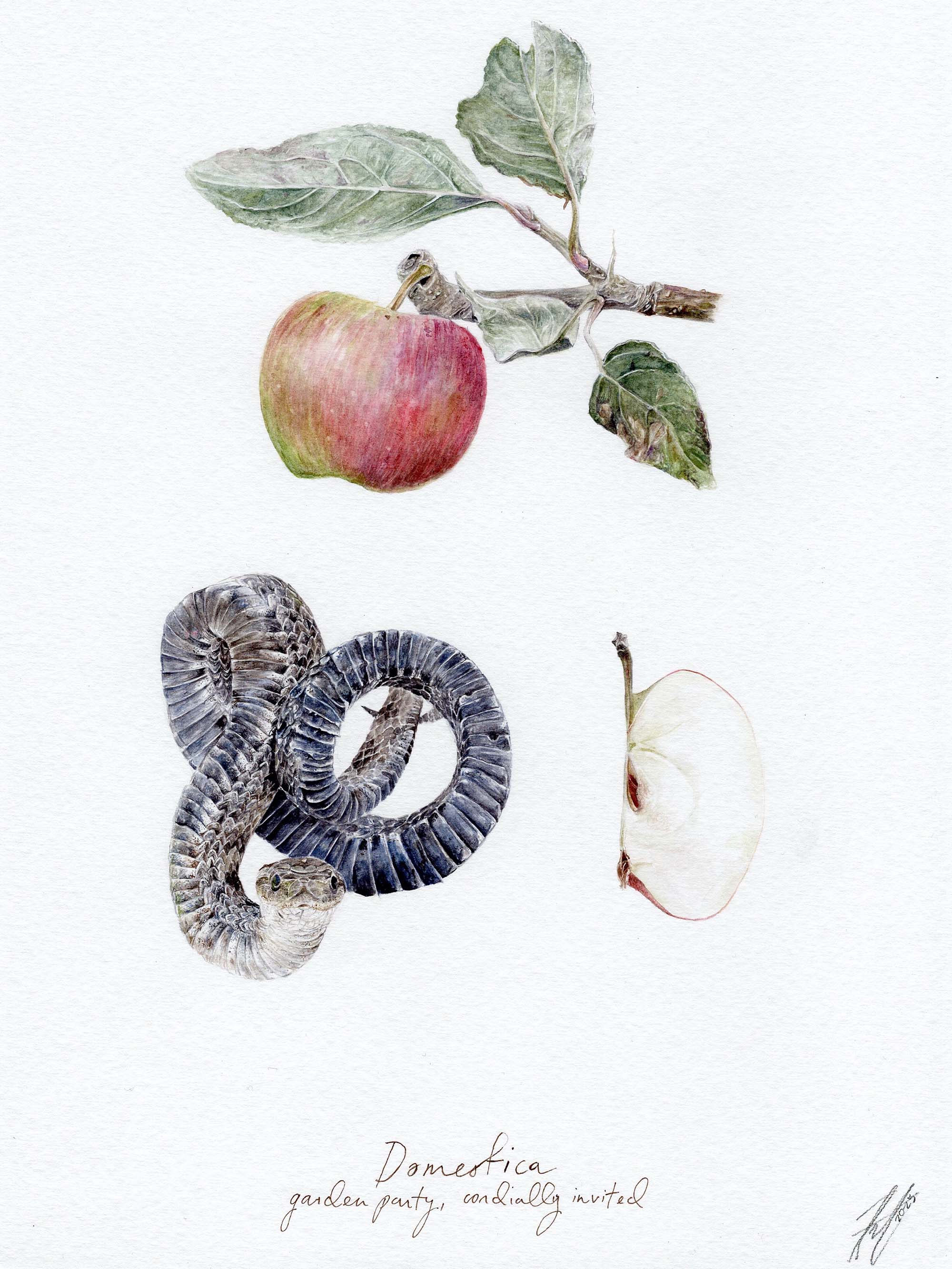

“Domestica” and “Recipe for a Patti” by Hashveenah Manoharan, both from the Butterfruit series. Images courtesy the artist.

The Tamil-Canadian artist is well aware of the importance of local, traditional ecological knowledge. She struggles with the idea that those stories and wisdom can disappear in the process of migration – a loss that parallels the erasure that happened under colonization. “There’s this feeling of knowledge being rusted away from you and possibly disappearing,” she says. Had her family not fled the civil war in Sri Lanka, Manoharan believes she would have inherited more of the regional stories and knowledge. “It’s just gone, and that wasn’t my choice,” she says.

Manoharan’s Butterfruit series is about the preservation of ecological memory. It’s rooted in grief about the loss of that knowledge, and is a way for her to archive the stories that she does have. “Archiving in itself is a reaction,” she says. “It’s an act of desperation.”

In the process, Manoharan has found hope. By being curious and attentive to the details of wildlife, carefully documenting it in detail and bringing in her own personal stories and history, she’s discovered that nature feels like home.

“The curiosity that helps you build nature literacy, that literacy of your natural environment, the power that comes with being able to name the things around you is familiarity. Familiarity is what makes home,” she says. “Comfort in nature is universal. And if nature is your home, you'll always be home.”

From September 18 to November 18, 2025, we invite artists throughout Canada to apply for the Rewilding Arts Prize. Five winners will each receive a $2,000 prize and be profiled by the David Suzuki Foundation and Rewilding magazine. Winners will also be welcomed into the growing Rewilding Arts Collective, a national network of artists advancing ecological awareness through creative practice.

A jury of artists, including winners from the inaugural prize, will select the recipients. For more information and to enter, visit davidsuzuki.org.

Comments ()