How former poachers are protecting Nigeria’s vanishing rainforest

Within the confines of Omo Forest Reserve, former hunters are now frontline rangers, leading grassroots rewilding efforts in one of West Africa’s surviving rainforests.

In the deepest parts of Omo Forest Reserve, Sunday Abiodun mounts foot and bike patrols carefully along the dangerous paths that wind through centuries-old trees. Just a few years ago, he was a routine hunter who killed pangolins and monkeys here with his locally made traps and dane guns. Things are different now. His tools serve a different purpose: that of dismantling cocoa farm camps in the forest, which for decades have threatened the reserve’s biodiversity. Abiodun’s transformation is part of several grassroots rewilding programs in one of Nigeria’s last remaining rainforests.

Omo Forest Reserve, the only such protected area in southwestern Nigeria, is globally recognised for its pristine biodiversity. Located in Ogun State, just 135 kilometres from the country’s largest city of Lagos, it has a rich green canopy that shelters endangered chimpanzees, white-throated guenons and some of Nigeria’s few surviving forest elephants.

But years of unregulated logging, cocoa farming and bushmeat hunting have punctured the heart of Omo. Cocoa farming in particular is a major threat because it drives forest clearing and illegal settlement, with farmers cutting down trees to plant cocoa despite the area’s protected status. Their activities destroy wildlife habitats, displace elephants and reduce the forest’s capacity to regenerate naturally.

This story follows Sunday Abiodun and other reformed hunters who are now working as rangers to prevent and reverse this damage by dismantling illegal farms, protecting endangered species and helping nature reclaim Omo’s once-lost wilderness.

From hunters to rangers

In Omo, Abiodun’s story is not isolated. He represents a growing number of reformed hunters who now dedicate their lives to protecting the very animals they once killed. Their reform began when the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF), an NGO that partners with the Nigerian government, started recruiting local hunters as rangers, offering them modest salaries and a chance to protect – rather than exploit – the forest. As a ranger, Abiodun always carries a machete in one hand and a musket over his other shoulder.

Before his transformation, Abiodun was never enthusiastic about conservation. In the past, he spent much of his rural life hunting the wild animals often referred to as “bushmeat” in local parlance. Now, at the age of 42, with years of experience as a hunter, he can easily identify every animal in the forest by name and knows where to find them whether grazing or drinking along the Omo river. Rare and endangered species like pangolin were highly prized and sought after when he was trafficking game.

For him, a typical day on patrol with other rangers focuses chiefly on locating cocoa farms, farmers’ camps and poachers, who use firearms to hunt indiscriminately in the forest.

The soil in Omo is rich with a dense tree-shade canopy, and it has been providing good conditions for growing cocoa for a long time. But growing cocoa in Omo is illegal under regulations of the state’s Ministry of Forestry.

Stakeholders blame the government for poor forest policy enforcement. Research by the Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan, shows that many cocoa farmers still hold the right to till the land despite the forest’s protected status.

The current tension in Omo revisits struggles in post-colonial conservation – where forests are now tightly regulated, often without community consensus. Many of the farmers have lived here for generations, and their eviction without formal land rights or alternatives only raises crucial questions about who gets to protect the forest – and who gets pushed out in the name of protection.

Omo forest covers about 1,305 square kilometres and is divided into different parts for easier administration. Only about 6.5 square kilometres of its “strictly protected zone,” believed to be elephant territory, is designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Yet, in order to protect wildlife and their shrinking habitat, more than 40 percent of the forest is now classified as a conservation zone, says Emmanuel Olabode, project manager for NCF.

However, Olabode emphasizes a point that rewilding might not have been as effective as what’s on ground today without the vital role being played by rangers, who are now the last line of defence for the protection of habitats of endangered wildlife. He adds, “If the forest is totally destroyed, we will never have elephants again.” He also says that rewilding Omo’s landscape has to do with letting nature, which has suffered terrible impacts from human encroachment, heal on its own. He and his colleagues are encouraging those who once hunted or cultivated the forest to take a turn around and act as its stewards.

Left: Erin camp. Photo courtesy Omo Forest Rangers. Right: A group of rangers. Photo: Temiloluwa O. Bamgbose.

Inside rangers’ camps

Abiodun, who formally joined in 2017, believes that a team of 12 rangers is far too small to cover the vast swaths of the Omo Forest Reserve. In the deeper parts of the elephant zone, rangers have set up nondestructive camps as temporary bases for each time they return from patrols. Basically, two or three teams follow a roster every week and throughout the period of stay in the heart of the forest, everything is planned and taken care of at this place. The teams rely on portable solar gadgets to light up the camp at night as they sleep in makeshift tents, usually surrounded by a chorus of birds and insects and soaked in the subtle sounds of windfall fruit.

“It takes us about one hour from our administrative office to reach these camps. The road always gives us trouble, it is muddy, making it quite difficult for us to get there by motorcycle when it rains,” Abiodun recounts.

Revealing some of the challenges the rangers are currently facing, one of the NCF’s directors, Memudu Adebayo, says the rangers’ work is exhausting amid other hiccups being experienced daily. However, they have a better life now than when they were poachers, he says. Before, they could go hunting for up to 10 days for nothing. “Today they can provide food for their families with a modest salary, and added to that, they’re doing something really good for the environment.”

Adebayo further mentions that this must be achieved to solidify ongoing efforts for the conservation of forest elephants. “We regard them as a part of our cultural identity and once we lose them, we can’t get them back,” he says. “Actually, rewilding is not just about wild animals,” he adds. “It’s also – and importantly – about refixing a relationship between people and their land, especially one that’ll sustain them for a long time.”

Deforestation and cocoa

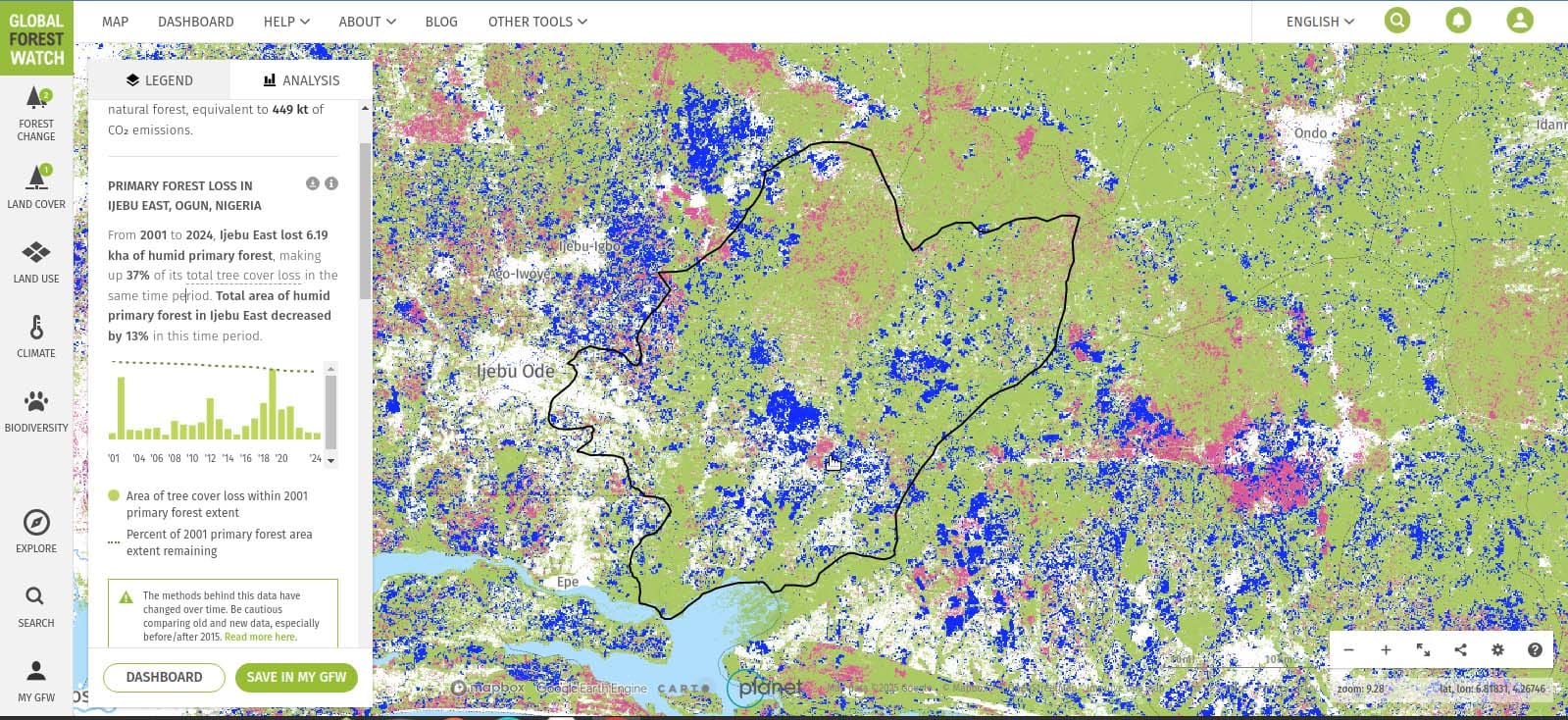

This forest was granted official protection in 1952. But between 2001 and 2024 alone, the area lost 61.9 square kilometres of humid primary forest, or up to 37 percent of tree cover, according to data from the Global Forest Watch. This scary level of ecological collapse hasn’t stopped, and with only a small number of rangers expected to patrol the length and breadth of the forest, the challenge of protecting it still stares in the face.

That said, it’s no surprise that conservationists sense a storm approaching as trees in the forest continue to disappear. In spite of the damage taking place, loggers are pressing on into the relatively small conservation area, mostly in search of precious wood. Logging remains a troublesome problem for wild animals that solely depend on trees for food, water and shelter, and rangers say the presence of chainsaws alone is enough to chase them away.

When policy fails

“Hunters have now stopped intruding during the day but still hunt in the night,” says one of the rangers working in the reserve. “While we were asleep, we heard gunshots around the strictly protected area. They’d hunt in pitch dark and leave before dawn.” Between 2019 and 2021, according to the Elephant Protection Initiative, who work to secure the survival of Africa’s elephants, four elephants were illegally shot dead in the Omo forest.

In the past, finding hunters’ footprints in the forest was not a Herculean task, but now, it’s difficult with the tougher patrols at night, Olabode says. “Most times we don’t encounter bullet casings, traps or footprints after hours of patrols. What we often find instead are animal trails.”

He says that sometime last year, they encountered several signs of hunting in the forest. But happily, due to their unrelenting pursuit of poachers, wild animals that had left the forest have slowly been returning to areas within the reserve where they feel safer.

Elephants and Omo’s return

“Recently, there’ve been no records of elephant poaching incidents in the forest,” Olabode says.

As such, in areas that have suffered logging, young native trees now bloom toward the sky. The forest proudly harbours more than 200 tree species, in addition to 100 species of birds and mammals – some of which can only be found in Omo. In fact, the rangers spoke about signs of renewal such as fresh elephant dung and the distant calls of guenon monkeys echoing through places that had long been silent. Elephants help to maintain forest health, as they consume tons of vegetation and their dung is full of seeds from the plants that they eat. As they roam large distances, they distribute seeds that go on to germinate into grasses, shrubs and trees.

“Rangers are working day and night to dismantle all illegal cocoa farms and plant native trees in their place,” says Abiodun. Camera traps planted by rangers show forest elephants are returning to these regrown patches. It gives encouraging signs that Omo is surviving, and gradually flourishing once more.

Efforts made thus far have helped in protecting critical wildlife habitats, which include a 375-square-kilometre sanctuary within the forest. Here, rarely seen species such as dwarf crocodile, hingeback tortoise and the majestic Ibadan malimbe, a native red-and-black weaver bird, are returning to the forest too. Having noticed that, the NCF is doing as much as it can to lead biodiversity monitoring together with wildlife researchers to ensure the ecosystem remains healthy and naturally intact.

The battle is still ongoing, but Abiodun and other rangers – and community members – have hope for the future. Across the country, many rewilding programs aimed at reversing years of forest destruction are gaining attention, but Omo stands out for the level of success already achieved and for its ability to continuously build trust in the process. “I used to believe the forest’s resources were endless and meant only for our use,” Abiodun says. “But now I realize that if we don’t take action to protect them, future generations may not learn anything about Omo.”

Comments ()